This is a longer post than is usual for this site but we (that’s Dawne Bell, Matt McLain and David Wooff) think it’s worth a read because it is clear that D&T can’t stay as it is and the post deals with the possible future nature of D&T.

Amid our growing concerns for the continued decline of design and technology education within the school curriculum, last year we instigated a programme of research which sought specifically to illuminate stakeholder perspectives from the community about the potential future of design and technology. Building upon aspects of our previous work, which was noted within an earlier blog post on this site, acting as a catalyst, this new line of enquiry was swiftly followed by the instigation of a ‘state of the nation’ national survey by the Design and Technology Association (DATA) and The Royal Academy of Engineers (RAE), and amid this groundswell of support, this renewed interested prompted the Head of Ofsted Amanda Speilman’s public address in support of the subject at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (Spielman, 2019). Having presented the initial findings of our research programme at a national (UK based) conference in May, we subsequently published our first phase findings to the International community in Malta at the PATT Conference in June. The paper was very well received and has sparked further debate and, pending publication of the full paper, further work is already in progress.

Hence it is timely to present an update, an interim report of our current work and as such we are delighted, once again be invited by David and Torben to pen this second blog post.

For context, as a gentle reminder before presenting our update we feel it would be useful first to present a brief overview of the national context. Beginning with the removal of mandatory study at key stage in 2004, in England design and technology has been in decline for the last 15 years. Successive governmental reforms have each taken their toll, including most recently the subject’s exclusion from the EBacc. Practical and creative subjects like design and technology offer a rich experience and within the context of a broad and balanced curriculum (McLain et al., 2019) and make a unique contribution (Irving-Bell et al., 2019). However, framed by weak external boundaries (Bernstein, 1971, 1975, 1990, 2000), with ‘weak epistemological roots’ (DfE, 2013, p.234), subject to constant change (Mitcham, 1994; Bell et al. 2017), within a knowledge focused curriculum (Gibb, 2016, 2017) which fails to recognise the contribution this creative subject makes, design and technology will always be subject to disadvantage. As such, there is, and will always be work to be done to ensure those outside the subject understand the contribution this extraordinary subject can and does make.

In advocating the importance of such a subject to exist within the curriculum, in other recent work we have sought to illuminate the subject’s necessity, through our exploration of technology as a fundamentally human and humanising activity which is inextricably linked to our evolution as a species and hence to the development of our societies (McLain et al., 2019). And it is from this perspective that we argue that drawing on a wide range of knowledge and values, through designing technological objects, every student should have the opportunity to engage with technological activity.

In our previous post, we made clear the need to do something bold and significant if we are to have any hope of reversing the subject’s deterioration. Invited by David and Torben who of course have themselves written several exceptional thought provoking think pieces (Barlex, 2017; Barlex and Steeg, 2017), we wrote this blog post to prompt further debate, to keep the subject at the forefront of current discourse.

We see that there are frequent juxtapositions between the nature of design & technology and the subject’s fundamental intentions but wonder whether these are sufficient for the future development of the subject. Given our passion for the subject, and in the spirit of the living document approach we have adopted, we challenged the community to transcend current and historic understandings of design and technology.

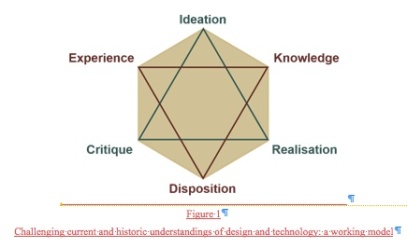

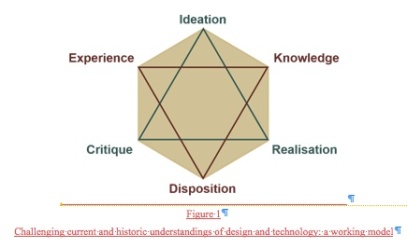

Evolved from research findings (Irving-Bell et al., 2019) Figure 1 is presents as a vehicle to instigate debate; the tensions and challenges, many of which are rooted in design and technology’s complex history and lie within the subject’s very heart. With full detail available in the paper, a brief articulation of each outcome is presented below:

- activity (ideating, realising and critiquing)

- curriculum intentions (knowledge, experience and dispositions)

- tensions created by the subject’s relationship with materials and the STEM agenda

Activity: Under the outcome ideation and critique, design and technology is conceived as a subject which transcends traditional material areas. Focuses on the creation of authentic opportunities, contextualised within society, for learners to engage in speculative questioning and deferred judgement. Students are always being encouraged to consider alternative technological solutions to human centric problems; be mindful of the impact and consequences technological innovations may have; be open-minded in the generation of solutions; give meaning through their ideas’ connections to the past; to recognise and acknowledge the folly in creating unneeded solutions. Within realisation this included the development of autonomy and confidence building, eye-hand co-ordination, manual dexterity and fine motor skills. There is something unique about making, the ability to manipulate, to control a material to create an artifact that is cited as being a transformative pedagogy (Irving-Bell et al., 2019).

Within curriculum intentions a series of desirable dispositions for learners emerged. These included team building, communication and collaboration. Resilience, and the development of an ability to take informed risks and engage in ‘proud failures’ was also cited by participants. Experience emerged in relation to what learners ‘do’, what they experience, and what is important to know. This included authentic approaches to problem solving and an awareness of human needs and wants within a technological society. The working knowledge of materials alongside the development of physical skills including manual dexterity. Within this context knowledge extended beyond the boundaries of the subject and related political and global agendas, and included knowledge for action and situated knowledge, within the context of other subject disciplines.

Tensions: Commonly held tensions focused around political drivers, fiscal demands and constraints and the academic versus vocational debate and design and technology’s vocational heritage.

If the subject is to move forward in response to the challenge presented in Figure 1 it will be important that we acknowledge an underpinning of the subject by these features, celebrating the interdisciplinary strength of the subject, calling on knowledge, understanding, skills and values from within and outside itself AND include the diversity of the historic individual disciplines without this manifesting itself as division. Such division serves no other purpose than to further weaken the subject’s position in that it fragments any possibility of an holistic, coherent approach.

As always, comments welcome

Acknowledgement

Once again, we would like to thank everyone from the community who responded to our call, and for their support and continued encouragement

For access to the full conference paper please visit this link:

https://research.edgehill.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/20775897/PATT_37_Malta2019_Proceedings.pdf

Irving-Bell, D., Wooff, D., & McLain, M. (2019). Re-designing Design and Technology Education: A living literature review of stakeholder perspectives. Paper presented at the PATT 37 Conference, Developing a knowledge economy through technology and engineering education, University of Malta, Msida Campus.

Key references

Barlex, D. (2017). Design and Technology in England: An Ambitious Vision Thwarted by Unintended Consequences. In M.J. de Vries (ed.), Handbook of Technology Education, Springer International Handbooks of Education, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-38889-2_11-1

Barlex, D. and Steeg, T. (2017). Re-Building Design and Technology In the secondary school curriculum, Version 2, A Working Paper. Available at https://dandtfordandt.wordpress.com/ Last accessed 31st March 2019.

Bell, D., Wooff, D., Mclain, M., and Morrison-Love, D. (2017). Analysing Design and Technology as an educational construct; an investigation into its curriculum position and pedagogical identity. Curriculum Journal. pp. 1-20. ISSN 0958-5176

Bernstein, B. (1971). On the Classification and Framing of Educational Knowledge. In M. Young (Ed.), Knowledge and Control. New Directions for the Sociology of Education (pp. 47-69). London: Collier-Macmillan

Bernstein, B. (1975). Class, codes and control: Towards a theory of educational transmission (Vol. III). London: Routledge.

Bernstein, B. (1990). The structuring of pedagogic discourse: Class, codes and control (Vol. IV). London: Routledge.

Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, research, critique (revised edition). New York: Rowman and Little.

DfE (2013). National curriculum in England: framework for key stages 1 to 4. London: Department for Education Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-framework-for-key-stages-1-to-4.

DfE (2014). The national curriculum for England to be taught in all local-authority-maintained schools. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/national-curriculum Last accessed 31st March 2019.

Gibb, N. (2017). The importance of knowledge-based education: School Standards Minister speaks at the launch of the ‘The Question of Knowledge’ [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/nick-gibb-the-importance-of-knowledge-based-education

Gibb, N. (2016). Nick Gibb: what is a good education in the 21st century? [Speech]. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/what-is-a-good-education-in-the-21st-century

Irving-Bell, D., Wooff, D., & McLain, M. (2019). Re-designing Design and Technology Education: A living literature review of stakeholder perspectives. Paper presented at the PATT 37 Conference, Developing a knowledge economy through technology and engineering education, University of Malta, Msida Campus.

McLain, M., Irving-Bell, D., Wooff, D., & Morrison-Love, D. (2019). How technology makes us human: cultural and historical roots for design and technology education. Curriculum Journal. doi:10.1080/09585176.2019.1649163

Mitcham, C. (1994). Thinking through technology: a path between engineering and philosophy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Spielman, A. (2019). Amanda Spielman speaking at the Victoria and Albert Museum (speech transcript). Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/amanda-spielman-speaking-at-the-victoria-and-albert-museum

A few years ago, I met Maggie Philbin from TeenTech www.teentech.com at a STEM conference we held at the University of Roehampton. Instantly inspired by her passion for STEM, her want to reach those children who would not even dream of a career in STEM as they felt it so out of their reach, I wanted in. Roehampton has been running a City of Tomorrow event each year with upwards of 300 pupils and student teachers participating to create the cities of the future, which will be smarter, kinder and safer. Pupils from year 6 and year 7 come together as engineers, designers and creative teams to design eco-friendly future proof communities.

A few years ago, I met Maggie Philbin from TeenTech www.teentech.com at a STEM conference we held at the University of Roehampton. Instantly inspired by her passion for STEM, her want to reach those children who would not even dream of a career in STEM as they felt it so out of their reach, I wanted in. Roehampton has been running a City of Tomorrow event each year with upwards of 300 pupils and student teachers participating to create the cities of the future, which will be smarter, kinder and safer. Pupils from year 6 and year 7 come together as engineers, designers and creative teams to design eco-friendly future proof communities. Their Festival Days bring together Science and Tech Industries that run workshops and experiments for the pupils to participate and engage with, the sheer wonder of it all is amazing. Voting buttons guage the pupils understanding and their interest in a STEM career at the beginning and end of the day. 53% of pupils say they are fairly or very interested in a STEM career but this rises to 73% by the end of the day. The events open their minds to the idea that any individual can succeed in this industry if they wish to. Exhibitors include, Siemens, Rolls Royce, Atkins, Airbus, Google, JVC, Accenture, Bae Systems, Universities, EDF, ConnectWise and Symantec to name but a few.

Their Festival Days bring together Science and Tech Industries that run workshops and experiments for the pupils to participate and engage with, the sheer wonder of it all is amazing. Voting buttons guage the pupils understanding and their interest in a STEM career at the beginning and end of the day. 53% of pupils say they are fairly or very interested in a STEM career but this rises to 73% by the end of the day. The events open their minds to the idea that any individual can succeed in this industry if they wish to. Exhibitors include, Siemens, Rolls Royce, Atkins, Airbus, Google, JVC, Accenture, Bae Systems, Universities, EDF, ConnectWise and Symantec to name but a few. The TeenTech Awards, which I judge and give feedback to teams, is so inspiring and the creativity of the pupils and their determination to succeed is infectious. This project is for 11-16 and 16-19 students, many of whom have grown up and been encouraged by other TeenTech events. The best projects go forward to the TeenTech award final at the IET London for judging and each winning team gets £1000 for their school. Some schools around the country have embedded the awards scheme into their subject curriculum, engaging even more pupils. One such school is Evelyn Grace in Brixton.

The TeenTech Awards, which I judge and give feedback to teams, is so inspiring and the creativity of the pupils and their determination to succeed is infectious. This project is for 11-16 and 16-19 students, many of whom have grown up and been encouraged by other TeenTech events. The best projects go forward to the TeenTech award final at the IET London for judging and each winning team gets £1000 for their school. Some schools around the country have embedded the awards scheme into their subject curriculum, engaging even more pupils. One such school is Evelyn Grace in Brixton.

Which brings me to

Which brings me to  In the book he describes four types of graphic organiser for presenting information/story telling – Chunking, Comparing, Sequencing and Identifying Cause and Effect. These are all simple to draw and with training I think learners would be able to use them fluently as the main means of developing their contextual challenge portfolios. And I think they would enjoy it.

In the book he describes four types of graphic organiser for presenting information/story telling – Chunking, Comparing, Sequencing and Identifying Cause and Effect. These are all simple to draw and with training I think learners would be able to use them fluently as the main means of developing their contextual challenge portfolios. And I think they would enjoy it. On 10 July Amanda Spielman, the head of Ofsted, gave a

On 10 July Amanda Spielman, the head of Ofsted, gave a

I really enjoyed your chapter. Thank you for reading so closely and taking my ideas seriously. Your chapter reminded me I should try to write up a simple version of my ideas teachable to kids. It’s a great challenge. I did write up some practical tips for techno-literacy but more is needed.

I really enjoyed your chapter. Thank you for reading so closely and taking my ideas seriously. Your chapter reminded me I should try to write up a simple version of my ideas teachable to kids. It’s a great challenge. I did write up some practical tips for techno-literacy but more is needed. Kevin is unashamedly optimistic about technology and how it will be beneficial to humanity. But I found another philosopher who is less sanguine. Her name is Shannon Vallor, Regis and Dianne McKenna Professor in the Department of Philosophy at Santa Clara University. She has written a fascinating book

Kevin is unashamedly optimistic about technology and how it will be beneficial to humanity. But I found another philosopher who is less sanguine. Her name is Shannon Vallor, Regis and Dianne McKenna Professor in the Department of Philosophy at Santa Clara University. She has written a fascinating book