Alison Hardy has written an intriguing piece in the latest edition of D&T Practice on the use of design fiction to teach about new and emerging technologies. She goes to some length to explain the nature of design fiction but does not provide an actual example of a piece of design fiction as written by a secondary school student although she indicates that in a follow up piece Natalie Cooke will describe how she has used design fiction in her year 9 lessons to teach about robotics and artificial intelligence. So in a way the piece by Alison is a bit of a teaser. I’m really looking forward to seeing Natalie’s piece in the hope that there will be examples of student’s design fiction. Having followed the link provided by Alison to James Auger and Julian Hanna’s piece on design fiction it seems to me that in its purist form design fiction is a very big ask. To quote:

Design fiction starts with the storyworld. The artefacts follow, designed for that world like props in a film. The main reason for developing a storyworld – in the design fiction approach – is to provide a new context or set of circumstances to design for.

Auger and Hanna present the idea of developing a storyworld through changing a significant event in history. They ask what would have happened if Jimmy Carter had won the presidential election in 1980 as opposed to Ronald Reagan. The storyworld here simply provides a logic to furnish an alternative history in which large resources are funneled into renewable energy. They have a similar agenda for their own work: to develop a storyworld framework to inform the design of an alternative energy infrastructure.

Science fiction often creates ‘alternative histories’. One of my favourites is Pavane by Keith Roberts which starts with the assassination of Elizabeth I and describes the result as a 20th century England in which the Roman Catholic Church is in control, with bans on innovation, particularly electricity, leading to a roughly mid-19th century technology with steam traction engines and mechanical semaphore telegraphy. Over all, the long arm of the Popes reached out to punish and reward; the Church Militant remained supreme. But by the middle of the twentieth century widespread mutterings were making themselves heard. Rebellion was once more in the air . . . It’s a rollicking good read and now acknowledged as one of the finest of all ‘alternate histories’.

So I have some questions.

- What does a teacher have to do to enable students to create a suitable storyworld?

- Does the teacher create a series of What if questions about what might be different in the world now if something significant had happened differently in the recent past?

- Or does the teacher take a short leap into the future and ask the students to imagine a world in which a particular new and emerging technology has developed to the point where it is widespread or even ubiquitous?

- In pursuing design fiction is the teacher trying to teach something specific about new and emerging technologies e.g. What counts as a robot? What are the limitations of currently available AI algorithms?

And once we have a storyworld the students then have to design artefact and systems to operate within this world and speculate about the way this plays out for the various actors within this world.

I’m not sure I agree with Alison in the distinction she makes between design fiction and science fiction. Her point is that in design fiction the reality is known whereas this is not the case for science fiction. Yes it is known but it is a speculative construct developed to explore the impact of designs within that reality. I think one might apply that to science fiction especially that sort of science fiction that focuses on what might happen 10 – 20 years hence. But this is a minor point and I want to finish on the value of science fiction with regard to developing the creative imagination. Some science fiction writing becomes science fiction films in which the various artefacts described in words have to be visualised and prototyped. Dune, based on the novel of the same name by Frank Herbert and Blade Runner, based on the novel Do Androids dream of electric sheep? by Philip K Dick are two important examples. The still suit which the Fremen in Dune use to recycle their body water is a wonderful example of prototyping in a storyworld and quite accessible to KS3 students. How the designers and prop makers develop and realise their ideas that eventually reach the film set provides an interesting story for students.

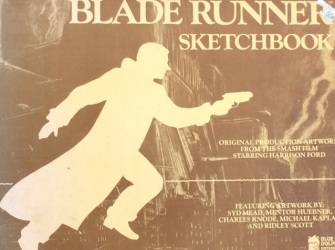

I have The Blade Runner Sketchbook which shows lots of preliminary sketches for the items that were so significant in the film – well worth sharing with students to show virtuoso sketching; there is artwork from Syd Mead and Ridley Scott amongst others.

I have The Blade Runner Sketchbook which shows lots of preliminary sketches for the items that were so significant in the film – well worth sharing with students to show virtuoso sketching; there is artwork from Syd Mead and Ridley Scott amongst others.

Some science fiction starts as films. I think this is the case for Star Wars. The most iconic figure in this saga must surely be Darth Vader. His mask has become a world wide symbol for tyranny yet it did not start out as a mask but a helmet along Samurai Warrior lines. It was Ralph McQuarrie, a concept artist working on the first film, who suggested that it should become a mask; a suggestion taken up by George Lucas. I wonder if science fiction stories might provide the stimulus for young people to create storyworlds for which they design?

Some science fiction starts as films. I think this is the case for Star Wars. The most iconic figure in this saga must surely be Darth Vader. His mask has become a world wide symbol for tyranny yet it did not start out as a mask but a helmet along Samurai Warrior lines. It was Ralph McQuarrie, a concept artist working on the first film, who suggested that it should become a mask; a suggestion taken up by George Lucas. I wonder if science fiction stories might provide the stimulus for young people to create storyworlds for which they design?

As always comments welcome.

You must be logged in to post a comment.